During an interview, Bill Gates and Warren Buffet were asked to choose a superpower that would ‘upgrade’ their lives. Both independently gave the same answer: “Being able to read super fast.” Buffet added, “I’ve probably wasted 10 years reading slowly.”

The word “read” means “to guess” (you can verify this in a dictionary). Therefore, one could argue that reading is an exercise in rapid guessing. Words combined in various ways can convey an infinite number of meanings and messages. Consequently, reading becomes a practice in “meaning making”; we navigate through countless combinations of meaning, honing our ability to interpret the world more quickly and flexibly —essential skills for making informed and skillful decisions.

When you encounter text on a page or screen, you might wonder, “What do these words mean, in contrast to everything I’ve learned before?” If the text is particularly persuasive and introduces new ideas, it might prompt you to question your existing knowledge and reflect, “How well does my current worldview align with reality?”

The challenge of reading an entire book lies in the ability to process another person’s system of “reference points of reality” through your own interpretative lens. In doing so, we temporarily adopt the author’s perspective, gaining insight into their understanding of reality and making contact with their “spirit.” This deep engagement provides an opportunity to truly comprehend another person’s worldview.

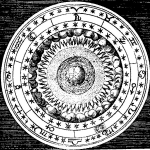

When I immerse myself in reading, especially with classical texts, I time after another encounter passages that resonate more profoundly than the rest. These moments are experienced as if they are in harmony with a timeless, higher order of existence, evoking memories of a primordial state of being.

In The Spirit of Adventure, The Guide